European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) enjoys a near-mythical status on restaurant menus. “Wild seabass” suggests pristine seas, skilled fishermen and superior taste. “Farmed seabass” is often presented as the more mundane alternative: predictable, cheaper and industrial. But the real story behind seabass on the European plate is far more complex — and at times uncomfortable.

Inspired by investigative journalism such as the Dutch TV programme Keuringsdienst van Waarde, this article explores where seabass really comes from, how it is produced, and why consumers, chefs and retailers should ask tougher questions about what they are buying.

A fish with two lives

European seabass is native to the eastern Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. In the wild, it thrives in coastal waters, estuaries and lagoons. Juveniles often grow up in brackish environments, while adults move offshore. This ecological flexibility is one of the reasons seabass became such an attractive species for aquaculture.

Today, the majority of seabass sold in Europe is farmed. Greece and Turkey dominate production, followed by Spain, Italy and France. Fish are typically raised in open sea cages, fed formulated diets and harvested year-round. From a supply-chain perspective, farmed seabass is a dream: stable volumes, consistent sizes and predictable prices.

Wild seabass, by contrast, is seasonal, scarce and expensive. Catches fluctuate heavily depending on weather, quotas and ecosystem conditions. That scarcity is exactly what fuels its reputation — and, unfortunately, its misuse as a marketing label.

When “wild” becomes a selling trick

The term “wild seabass” carries significant commercial value. In restaurants and fishmongers, it can easily justify prices that are two or three times higher than farmed fish. Yet investigations across Europe have shown that the line between wild and farmed is not always clearly drawn — and sometimes deliberately blurred.

Mislabeling can take several forms. Farmed seabass may be sold as wild, intentionally or through sloppy documentation. Imported fish can be relabeled with vague origin descriptions such as “Mediterranean seabass,” which sounds romantic but says nothing about production method. In more problematic cases, fish may be caught illegally and then passed off as legitimate wild catch.

For consumers, this is almost impossible to detect. Once a fish is filleted and plated, visual differences largely disappear. Taste differences, often cited as proof of wild origin, are subjective and unreliable.

The uncomfortable topic of illegal fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is a persistent issue in European waters, including for seabass. Despite quotas, minimum landing sizes and seasonal closures, illegal catches still enter the market. These fish often bypass official auctions and controls, finding their way into informal or opaque supply chains.

Ironically, illegally caught seabass can sometimes undercut legally caught wild fish while still being sold as “exclusive.” This creates a perverse incentive structure: honest fishermen struggle, while rule-breakers profit.

From a sustainability perspective, this is deeply problematic. European seabass stocks have been under pressure for years, prompting stricter management measures. Illegal fishing undermines those efforts and erodes trust throughout the sector.

Farmed seabass: unfairly dismissed?

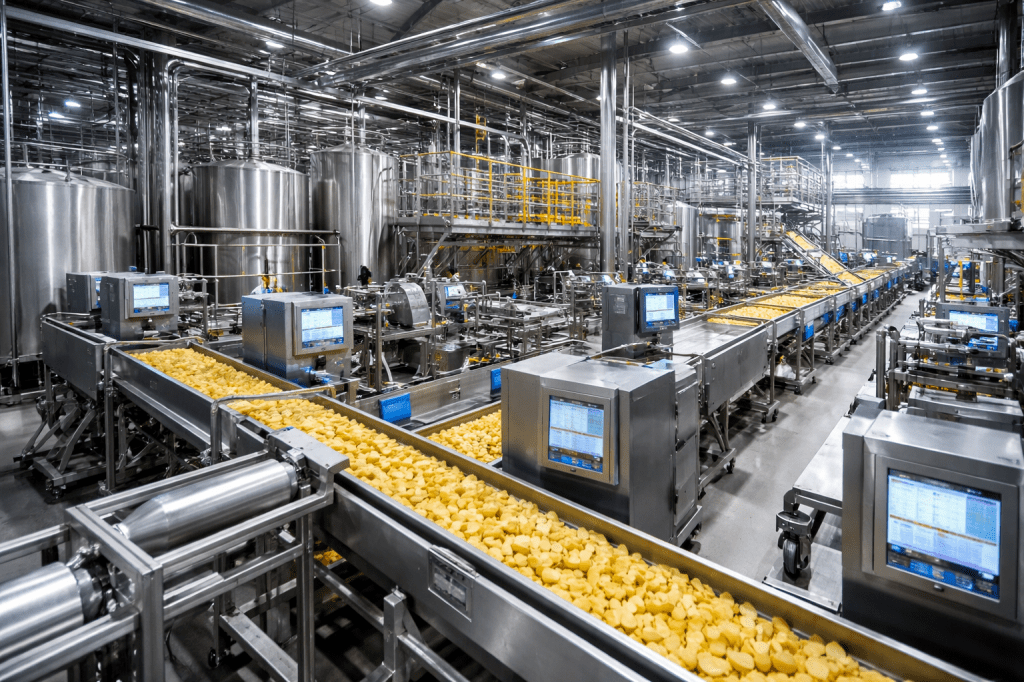

Public perception still tends to frame farmed seabass as inferior. That view is increasingly outdated. Over the past two decades, aquaculture technology has improved dramatically. Feed conversion ratios have dropped, fish health management has improved, and environmental monitoring around farms has become more sophisticated.

Farmed seabass today is not the same product it was twenty years ago. Texture, fat composition and flavour have become more consistent, and in blind tastings many consumers struggle to distinguish farmed from wild fish.

From a sustainability standpoint, responsibly managed aquaculture can actually reduce pressure on wild stocks. It offers traceability, year-round supply and a controlled production environment — all features that wild fisheries cannot guarantee.

That does not mean all seabass farming is automatically sustainable. Poorly managed farms can cause local environmental impacts. But dismissing farmed seabass outright ignores the real progress made in the sector.

Transparency as the real issue

The core problem is not whether seabass is wild or farmed. The real issue is transparency. Consumers should know what they are buying, where it comes from and how it was produced. Restaurants should be precise in their menu descriptions. Retailers should demand proper documentation. Regulators should enforce labeling rules consistently.

Clear labeling — wild or farmed, catch area, production country — would remove much of the confusion. It would also expose illegal practices more quickly and reward honest producers.

For chefs and food professionals, there is also an opportunity here. Instead of using “wild” as a vague quality signal, they can tell a more nuanced story: about seasonal wild fish when available, and about high-quality farmed seabass when it is not.

A fish that reflects the food system

European seabass is more than just a popular menu item. It is a mirror of the modern food system, where sustainability, scale, regulation and consumer perception collide. Romantic ideas about wild fish coexist with industrial realities. Good intentions mix with questionable practices.

As investigative programmes like Keuringsdienst van Waarde have shown, asking simple questions — “Is this wild?”, “Where was it caught?”, “Who benefits?” — can reveal uncomfortable truths. But those questions are necessary.

Because in the end, the choice is not between wild or farmed seabass. The real choice is between a transparent, accountable seafood system — or one where labels mean little and trust slowly erodes.

Leave a comment