If you buy a tomato, cucumber, or pepper in the United States, there’s a good chance it started its journey in one small Canadian town just across the border. Leamington, Ontario, has become the nerve center of North America’s greenhouse vegetable trade. But political turbulence in Washington is rattling the system.

Former President Donald Trump, back in the White House, has once again threatened to scrap existing trade agreements. For Canadian growers, the message is clear: without them, America’s salad supply chain grinds to a halt — but political games and unpredictable tariffs are forces few businesses can fully shield themselves against.

America’s Dependence on Its Neighbors

The U.S. simply doesn’t have enough domestic capacity to supply its own demand for greenhouse crops like tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, eggplants, and lettuce. Imports from Mexico and Canada are essential, governed by long-standing trade agreements — agreements now facing political attacks.

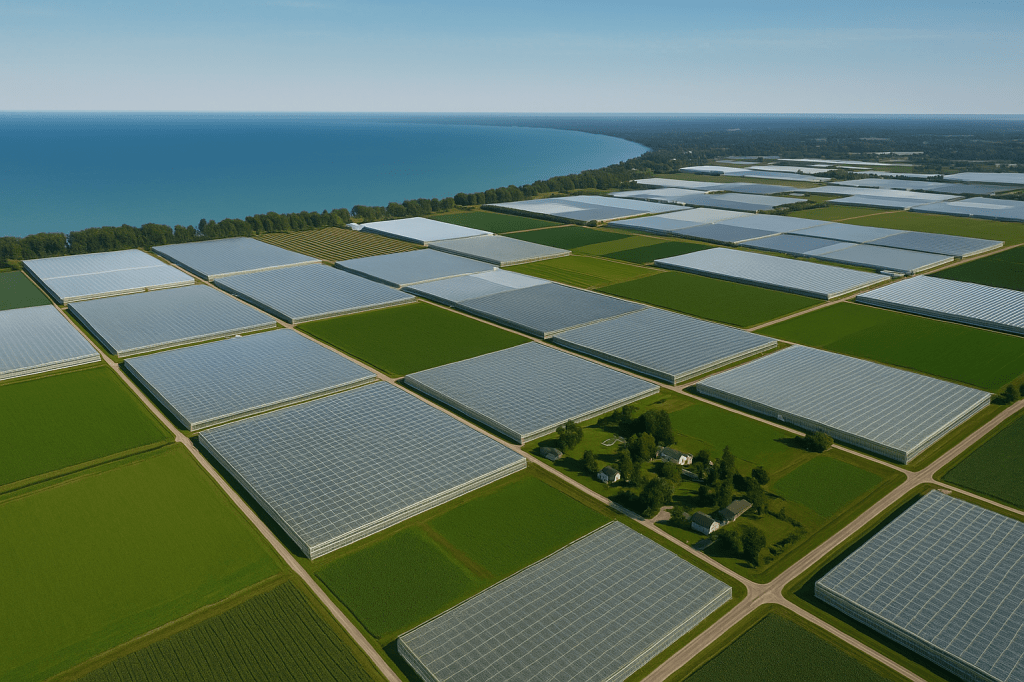

In Leamington, located on the shores of Lake Erie, growers and exporters coordinate the flow of greenhouse vegetables across the entire continent — Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. Without them, supermarket shelves across the Midwest and East Coast would be stripped of fresh salad vegetables. Demand for safe, high-quality greenhouse produce in the U.S. is rising, making this supply chain even more critical.

From Tomato Town to Continental Powerhouse

Leamington, nicknamed the “Tomato Capital of Canada,” owes its success to fertile soil, long growing seasons, and a mild climate. In the early 1900s, farmers planted open-field vegetables, later expanding into small greenhouses to extend the season. The arrival of a Heinz processing plant in 1910 supercharged local tomato production.

After World War II, waves of Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish immigrants brought expertise and entrepreneurial drive, building family farms that grew into multi-generational businesses. In the 1990s, Dutch greenhouse builders introduced cutting-edge technology, and after 2000, seasonal workers from Mexico became indispensable for labor-intensive tasks.

Today, Canada has 2,340 hectares of greenhouse vegetable production, most of it clustered around Lake Erie. Tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers account for 91% of output, with 90% exported to the U.S.

Mega-Growers and Year-Round Supply

Family businesses have evolved into industry giants — Mastronardi Produce, Nature Fresh Farms, Great Lakes Greenhouses, and Topline/Mucci Farms among them. They operate not just in Canada, but also in the U.S. and Mexico, ensuring flexibility when trade tensions shift the economic calculus.

Together with roughly 170 other growers, they form the Ontario Greenhouse Vegetable Growers (OGVG) cooperative. This collective approach enables year-round supply to major retailers like Walmart, Whole Foods, Wegmans, Trader Joe’s, and Sprouts. In winter, produce flows north from Mexico; in summer, it moves south from Canada.

These retailers prioritize consistent, food-safe supply and increasingly demand organic options — an area where Canadian growers offer more variety than many European counterparts. Health-minded U.S. consumers, even amid rising food prices, continue to pay for fresh produce, especially organics.

Why More U.S. Greenhouses Aren’t the Answer

It may seem logical for Canadian growers to expand in the U.S. to sidestep tariffs. In reality, several factors stand in the way:

- High costs — Building greenhouses in the U.S. is expensive, especially with import tariffs on Canadian aluminum.

- Labor challenges — U.S. labor is significantly more expensive, and the H-2A program for foreign workers mainly supports field agriculture, not year-round greenhouse work. Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program offers more stable labor from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, and beyond.

- Currency advantage — A weaker Canadian dollar, combined with U.S. dollar sales, gives Canadian producers a built-in price edge.

As a result, production costs in the U.S. can run 40% higher than in Canada. Canadian growers do maintain some U.S. greenhouses — mainly as “showcase” facilities to serve local-sourcing demands — but large-scale expansion south of the border remains financially unattractive.

Trump’s Push for System Change

What Trump is signaling isn’t just tariffs; it’s a call for a complete restructuring of America’s fresh vegetable supply. Experts estimate such a shift could cost tens of billions of dollars. To make it work, the U.S. would need to:

- Subsidize greenhouse construction and renewable energy systems (solar, geothermal).

- Overhaul restrictive state-level regulations.

- Invest heavily in automation to reduce labor needs.

Without a long-term master plan — complete with technology investment, energy strategy, and labor solutions — it’s unlikely the U.S. can replace its reliance on Canadian and Mexican imports anytime soon.

Leamington Holds the Cards

For now, Leamington’s growers have little to fear. The region’s deep knowledge, integrated supply chains, and year-round production capacity make it uniquely resilient. If tariffs shift the market, these companies can adjust production across their trinational operations faster than most competitors can react.

Still, Canadian producers are already weighing how to pass along any Trump-imposed costs to U.S. consumers. Margins in greenhouse farming are slim; absorbing the extra cost would weaken the entire cluster. That means higher prices at the checkout — or a drastic change to the American salad bowl.

If tariffs ever bite hard enough, Americans may face a stark choice: pay more for tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers… or get used to a salad made from cabbage, beets, and carrots.

Leave a comment